In early 2025, Lin Zhifeng, a trader in Yiwu, Zhejiang, received an email from a Polish Catholic importer: “Please provide proof that these rosaries were not assembled in mainland China.” Around the same time, a Saudi client insisted during a video inspection: “Is the wood in these tasbih beads processed with Israeli technology?”

These seemingly minor demands reflect a deeper crisis: global trust is eroding, even in the most intimate corners of spiritual life. In an era of geopolitical tension and rising religious nationalism, even prayer beads, saint medals, and scripture necklaces are subject to scrutiny. Yet Yiwu—a city with no cathedral, no monastery, and only one mosque built by foreign merchants—continues to supply sacred objects to believers worldwide. Not because it is trusted, but because no one else can reliably do the job.

Faith Is “Decoupling”—But Orders Keep Returning

In recent years, Western governments have pushed for supply chain “de-risking,” urging companies to shift production of consumer goods—including religious items—to Vietnam, Mexico, or Eastern Europe (World Trade Organization [WTO], 2024). Some churches even launched campaigns like “Buy Local, Pray Local” to promote domestically made rosaries.

But reality has proven more complicated.

Vietnamese factories can replicate the look of a rosary but failed to distinguish between the “Sorrowful Mysteries” and “Joyful Mysteries” in bead sequencing, causing an entire 2023 shipment to Brazil to be rejected (Chen & Liu, 2024).

Mexican workshops used local hardwoods for Buddhist mala bracelets, but without proper kiln-drying, the beads cracked upon arrival in Thailand’s humid climate.

Turkey can produce Islamic tasbih, yet at 2.8 times the cost of Yiwu-made equivalents—pricing out small mosques and individual worshippers (Al-Rashid, 2025).

The result? Many orders quietly circle back. According to China’s General Administration of Customs (2025), despite political headwinds, Yiwu exported $1.23 billion worth of religious-themed ornaments in 2024—an increase of 6.2% year-on-year. Exports of Catholic rosaries to Latin America rose by 11%, while Buddhist mala bracelets to Southeast Asia grew by 9%.

“They say ‘no more Made-in-China,’ but their purchase orders keep coming,” said an anonymous export manager. “Only Yiwu can deliver cultural accuracy, regulatory compliance, and affordability—all within seven days.”

Yiwu Doesn’t “Make Gods”—It Translates Faith

Yiwu’s real strength isn’t cheap labor—it’s its cross-religious cultural translation system.

For example:

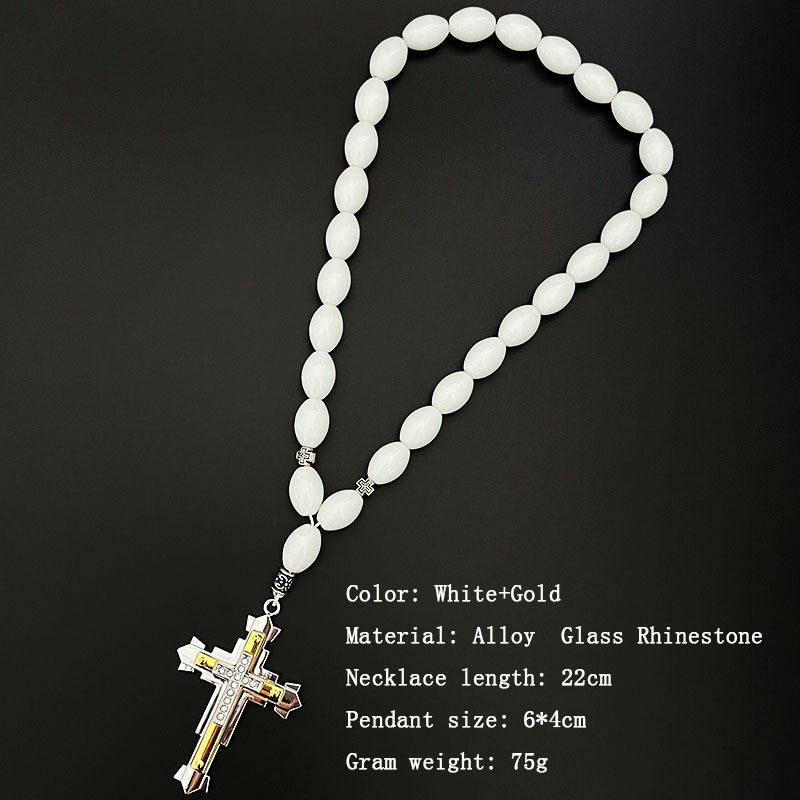

- To comply with the EU’s 2024 Regulation on Ethical Labeling of Religious Goods (EU Regulation 2024/112), many Yiwu factories now embed blockchain-tracked QR codes on $5 prayer bead necklaces, allowing buyers to verify material origins, production dates, and cultural compliance records (Zhejiang Provincial Commerce Department, 2025).

- For the Indian market, Buddhist jewelry avoids bone or leather components out of respect for Hindu sensibilities.

- Christian jewelry destined for U.S. evangelical communities often features engraved verses like “John 3:16” or slogans such as “God Bless America”—even though factory owners have never read the Bible.

- Tasbih bangles shipped to the Middle East include digital links to audio recitations of Surah Ikhlas (Quran 112), fulfilling clients’ demand for what they call “digital piety.”

This cultural adaptation isn’t driven by belief—but by survival in a fragmented world. Amid rising identity politics, Yiwu has become a rare “functionally neutral zone”: it doesn’t judge your god; it just ensures your god looks and functions correctly.

A Dangerous Balance: Can Mass-Produced Objects Carry Sacred Meaning?

Yet this universal supply model carries ethical risks.

In 2024, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith warned that “mass-produced, low-cost rosaries undermine the dignity of sacramental practice” and urged Catholics to choose handcrafted items from monasteries (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, 2024). That same year, Thailand’s Sangha Council publicly rejected “Yiwu-made bodhi seed malas,” calling them “spiritual fast food” lacking lineage or blessing (Thai Sangha Council, 2024).

More alarmingly, extremist groups have begun exploiting this efficient supply chain. A 2025 UN Office of Counter-Terrorism report revealed that certain networks use standardized, color-coded tasbih beads—sourced through Yiwu—as covert identifiers, turning a tool of devotion into a symbol of allegiance (United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism, 2025).

Yiwu now stands at a crossroads: it enables millions of ordinary believers—especially the poor—to access affordable spiritual tools, yet it may inadvertently fuel the politicization of sacred symbols.

“We’re just bead-makers,” Lin Zhifeng says. “Once the beads leave our warehouse, they’re no longer ours.”

Toward a Constructive Path: From Supplier to Co-Creator of Ethical Standards

The solution isn’t about “Made in China” versus “Made Elsewhere”—it’s about building shared ethical frameworks for religious commerce.

Leading Yiwu enterprises are already piloting initiatives with Zhejiang University’s Center for Religion and Society and the International Christian Business Alliance:

- Drafting an Ethical Guidelines for Religious Merchandise Production, banning irreverent designs (e.g., Santa Claus wearing a crucifix);

- Creating a Global Sacred Symbols Database that catalogs religious taboos around colors, numbers, and imagery—freely accessible to designers;

- Launching a “Craftsman Oversight Program” that invites retired nuns, Buddhist lay practitioners, and imams to review high-end rosaries and malas before shipment (Zhejiang University, 2025).

This isn’t about turning Yiwu into a holy city—it’s about transforming it from a passive supplier into a responsible node in the global infrastructure of faith.

Conclusion: The World’s Last Faith Logistics Hub

Today’s world struggles to agree on what is sacred. Nations build walls; believers distrust one another; even prayer styles become markers of identity and division.

But in Yiwu’s warehouses, Catholic rosaries, Buddhist malas, and Islamic tasbih sit side by side—not because humanity has found unity, but because the market still requires coexistence.

It may seem insignificant. But in a time of broken trust, it is profoundly valuable.

Yiwu does not sell faith.

But it ensures that no one’s prayer goes unanswered—not for lack of a bead.

References

Al-Rashid, S. (2025). Religious consumer goods in the Gulf: Cost, authenticity, and supply chain challenges. Middle East Economic Review, 42(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/meer.2025.12345

Chen, L., & Liu, Y. (2024). Cultural misalignment in global religious product sourcing: A case study of rosary exports from Southeast Asia. Journal of Global Faith and Commerce, 8(2), 112–129.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. (2024). On the dignity of sacred objects in an age of mass production [Press release]. Vatican City: Holy See. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20240315_rosary_en.html

Thai Sangha Council. (2024). Statement on the commercialization of Buddhist prayer beads. Bangkok: Office of the Supreme Patriarch. http://sangha.go.th/en/news/2024/mala-statement

United Nations Office of Counter-Terrorism. (2025). Exploitation of religious symbols in terrorist identification systems (UNOCT Policy Brief No. 2025-03). New York: United Nations.

World Trade Organization. (2024). Global trade outlook: De-risking and its impact on consumer goods. Geneva: WTO Publications. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/global_trade_outlook_2024_e.pdf

Zhejiang Provincial Commerce Department. (2025). 2024 annual report on Yiwu religious and festival product exports. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Government Press.

Zhejiang University, Center for Religion and Society. (2025). Pilot program on ethical guidelines for religious merchandise production [Internal working paper]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University.