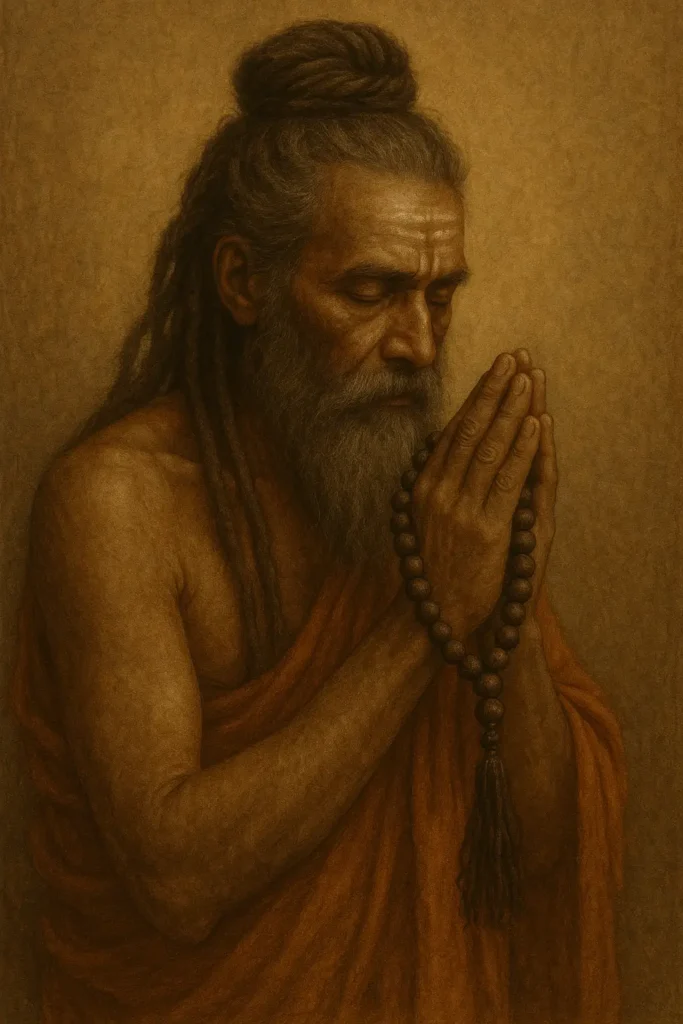

You’ve likely seen them—worn by monks in temples, carried by meditators, or even styled as mindful accessories in modern cities. Buddhist prayer beads, known as malas or japamalas, are far more than decorative objects. They are sacred tools of mindfulness with a history stretching back over 2,500 years.

But how did they originate? Why are they usually 108 beads long? And how did practitioners count repetitions accurately—long before digital counters existed?

As a team with over a decade of experience studying religious bead traditions across Asia and beyond, we’ve combined scriptural sources, historical records, and hands-on craftsmanship knowledge to bring you a clear, trustworthy guide to the origin, symbolism, and practical wisdom behind Buddhist prayer beads.

You’ve likely seen them—worn by monks in temples, carried by meditators, or even styled as mindful accessories in modern cities. Buddhist prayer beads, known as malas or japamalas, are far more than decorative objects. They are sacred tools of mindfulness with a history stretching back over 2,500 years.

But how did they originate? Why are they usually 108 beads long? And how did practitioners count repetitions accurately—long before digital counters existed?

As a team with over a decade of experience studying religious bead traditions across Asia and beyond, we’ve combined scriptural sources, historical records, and hands-on craftsmanship knowledge to bring you a clear, trustworthy guide to the origin, symbolism, and practical wisdom behind Buddhist prayer beads.

1. The Origin: A Direct Teaching from the Buddha

Rooted in Ancient India, Refined by Buddhism

The use of bead strings for counting mantras or prayers predates Buddhism. In ancient India (circa 5th century BCE), practitioners of Brahmanism and Jainism already used seed-based rosaries to track recitations.

Buddhism adopted and transformed this practice into a structured spiritual discipline. The earliest clear scriptural reference appears in the Chinese Buddhist text The Sutra of Mokurenzi Beads (Mokurenzi Jing), traditionally attributed to the 2nd-century CE translator An Shigao:

King Prasenajit (or Virudhaka), burdened by worldly duties and mental distress, asked the Buddha:

“Is there a simple method to purify my mind and reduce suffering while managing state affairs?”The Buddha replied:

“Take 108 seeds of the Mokurenzi tree (Sapindus), string them into a mala, and carry it with you at all times. While walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, recite the Buddha’s name with single-pointed focus—moving one bead per repetition. Through this practice, karmic obstacles and afflictions will gradually dissolve.”

This teaching marks the formal integration of the mala into Buddhist practice—not as a ritual ornament, but as a practical aid for mental discipline.

📌 Expert Note: Mokurenzi refers to the soapberry tree (Sapindus mukorossi), whose hard, smooth seeds were abundant in India. The name “Mokurenzi” (木槵子) literally implies “freedom from worry”—a fitting symbol for a tool meant to alleviate suffering.

2. Why 108 Beads? The Symbolism Behind the Number

The number 108 is deeply symbolic across Dharmic traditions. In Buddhism, it commonly represents:

- 108 Kleshas (mental afflictions): Derived from

6 sense organs × 3 types of feeling (pleasant, unpleasant, neutral) × 2 emotional tendencies (pure/impure) × 3 time periods (past, present, future) = 108. - 108 Dharmas or Buddhas: In some Mahayana texts, 108 signifies the totality of enlightened qualities.

- Cosmic harmony: Ancient Indian astronomy noted that the distance from the Earth to the Sun is roughly 108 times the Sun’s diameter—a celestial echo of balance and completeness.

Thus, completing one full round of 108 recitations symbolizes a complete cycle of purification.

3. How Did Ancient Practitioners Keep Count?

Without apps or clickers, early Buddhists relied on intelligent mala design:

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Guru Bead (Meru or “Buddha Head”) | The largest bead, marking the start and end. Traditionally, practitioners do not cross over this bead; instead, they flip the mala and continue in reverse to show reverence. |

| Marker Beads or Spacers | Often placed every 27 beads (108 ÷ 4), helping users divide the practice into manageable segments. |

| Counter Beads (or “Disciple Beads”) | Small secondary beads (usually 10) dangling from the guru bead, used to track completed rounds (e.g., 10 rounds = 1,080 recitations). |

💡 From Experience: In restoring 19th-century Tibetan and Chinese malas, we’ve observed that counter beads are often the most worn—evidence of daily, devoted practice over decades.

4. Ancient Craftsmanship: Simplicity with Sacred Intent

Early malas prioritized natural materials, purity, and function:

- Primary Materials:

- Mokurenzi (soapberry) seeds – the original choice per the sutra.

- Bodhi seeds – from the sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa), symbolizing enlightenment.

- Later additions: sandalwood, lotus seeds, crystal, coral, and rudraksha (in shared Hindu-Buddhist contexts).

- Craft Techniques:

- Hand-drilled holes using bone or metal awls.

- Polished by hand or with natural abrasives (sand, cloth).

- Strung on cotton, silk, or yak-hair cords—never synthetic.

- No artificial treatments: Traditional malas were undyed and unvarnished, reflecting the Buddhist ideal of non-attachment to form.

A well-used mala develops a soft luster over time—called patina or baojiang in Chinese—a visible testament to years of mindful repetition.

5. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Must a Buddhist mala always have 108 beads?

A: 108 is the standard, but shorter versions exist:

- 54 beads (half-mala)

- 27 beads (travel-friendly)

- 21 or 22 beads (common in Vajrayana rituals)

The key is focused repetition, not rigid adherence to number.

Q2: Is it appropriate to wear a mala as jewelry?

A: If used for spiritual practice, treat it with respect—avoid placing it on the floor, wearing it while sleeping, or using it purely for fashion. For decorative purposes, consider non-sacred materials (e.g., generic wood beads).

Q3: How do malas differ across Buddhist traditions?

- Theravāda (Sri Lanka, Thailand): Rarely uses fixed-count malas; emphasis on meditation over mantra.

- Mahāyāna (China, Japan): 108-bead malas for Buddha-name recitation (e.g., “Namo Amituofo”).

- Vajrayāna (Tibet, Bhutan): Often 108 or 111 beads, with guru bead, tassels, and sometimes a gau (amulet box).

Q4: What if my mala breaks?

A: In many traditions, a broken mala is seen as a positive sign—indicating the release of heavy karma or the completion of a spiritual cycle. Collect the beads respectfully and consider restringing or offering them at a temple.

Q5: How should I care for my mala?

- Keep it clean and dry.

- Avoid contact with perfumes, lotions, or excessive sweat.

- Store it in a cloth pouch or on a clean altar.

- Never lend it casually—malas absorb personal energy.

6. References (APA Style)

- An, S. (Trans.). (ca. 2nd century CE). Mokurenzi jing [The Sutra of Mokurenzi beads]. In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō (Vol. 17, No. 787). Tokyo: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai.

- Gethin, R. (1998). The foundations of Buddhism. Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, P. (2013). An introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, history and practices (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kieschnick, J. (2003). The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture. Princeton University Press.

About Us

Since 2012, ReligionRosary.com has been dedicated to the scholarly and respectful exploration of prayer bead traditions across Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and more. Our content is reviewed by religious scholars, master artisans, and longtime practitioners to ensure accuracy, cultural sensitivity, and practical value.